Urban Design Approach

At right is a narrative of our approach to urban design. Below shows the application of that methodology to two different projects: a CBD urban infill, and a plan for a new town. Move over the images to enlarge.

Examples of Project Phases

Historic Development

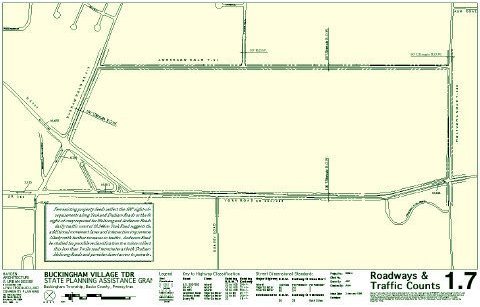

Transportation

Building Survey

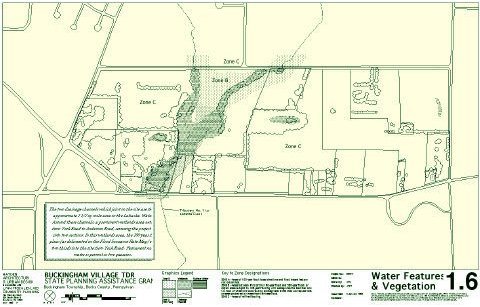

Existing Site Features

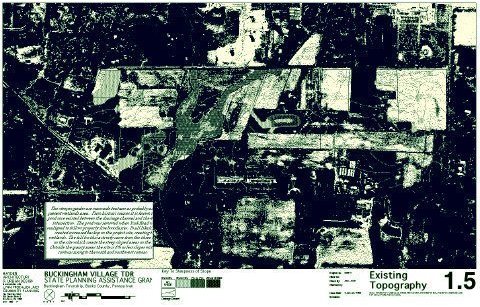

Existing Topography

Existing Infrastructure

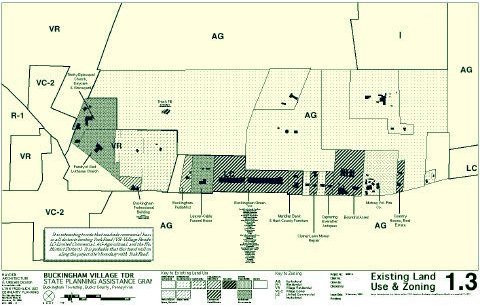

Existing Zoning

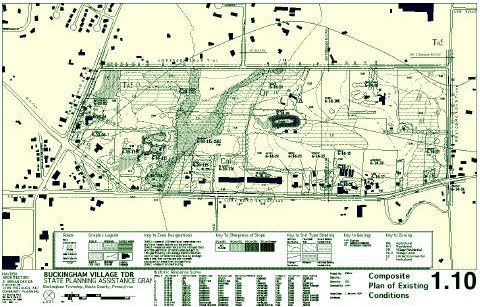

Composite Plan of Existing Conditions

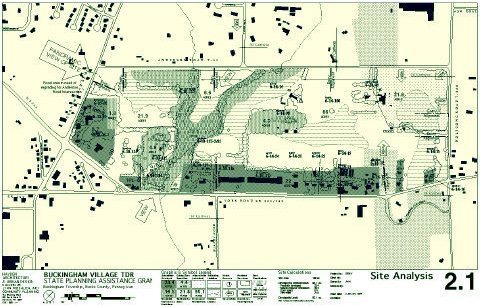

Site Analysis

Conceptual Master Plan

Design Guidelines

Urban Physical Form

The new streets and buildings of land development endure for generations, thus there is a great responsibility in establishing sustainable new land use patterns. Practitioners of urban design and in particular, neo-traditional land planners, have identified some impediments to the development of successful urban forms. These include past development and some zoning practices that have largely undermined the wide variety of town and building forms that were historically used. The integrated, pedestrian oriented, historical forms that created traditional villages, towns, and the core of some large cities, have been replaced with a single use / zoning model that is based on auto dependent / separated land uses, developed in the 1950s. The use of this model, especially in or near historic areas, does damage by conferring approval on intrusive forms that lack appropriate massing, scale, setback, and use kinship to the context area. In redevelopment and new development areas, this same model prohibits the creation of town forms and encourages isolated development. Urban design professionals are very aware of issues like these and work towards integrated sustainable community design.New community structures, streets, and cities need not look so dismal. Planners of new building design to urban development have a 'civic responsibility' to harmonize with the community, add positively to the fabric of the built environment, and contribute to the cultural heritage of future generations. This civic trust requires a responsible design method, creativity, and design integrity.

In the context of this responsibility, it would be a disservice to speculate on possible solutions based on incomplete data and mere assumptions that may later distract from developing a more fitting but less obvious solution. Thus we believe in a rational design process that provides the framework to address diverse and complicated program requirements for large scale projects, in order to create a solution crafted to fit the constraints and opportunities of the site and the goals of the client group and community. That approach is described below.

Design Method : Externalized Process

The design process has always been problematic to evaluate since it is typically internalized in the mind of the designer. As the scale of a project grows this process needs to be externalized in a cogent fashion to facilitate objective evaluation by other parties (particularly the client). At the scale of urban design projects, each step of the process needs to be clearly transparent to the client and convincing to future reviewers well after the service is complete. For this reason we will use the ‘rational’ methodology (adapted from Hamid Shirvani’s The Urban Design Process). In short the process follows a strict methodology:

We typically document the process in report format, so each step can be revisited and the lineage of the final solution traced. A carefully followed process shows the rational justification of some solutions and the logical exclusion of others, minimizing the bias of designer and client towards preconceived or rote solutions.

Design Method : Data Collection

The typical process of land use design is based on approximate or incomplete data that often leads the planner to erroneous initial layout decisions. The imposition of arbitrary, inappropriate, or hastily considered forms on communities and clients is unfortunate. To overcome this problem, the initial step is data collection, which must occur before the creative process to serve it’s intended purpose.

This seemingly dry process can lead to surprising findings that alter the course of a project. Take for example the Physical Master Plan for Pfeifle Field in Bethlehem, PA. In the ‘historical’ research of the site, the 1886 planned street layout was discovered. Since one aspect of the project was the subdivision of this multi-block area, the implementation of the original 1886 street grid became part of the proposal. The fulfillment of the historic plan for Bethlehem enhanced the credibility to the proposal for many. In another example, research in preparation for the design of a new town in Pennslvania, local historical deed descriptions were found that used a land measurement called a "perch" which was equal to 16.5 feet. This led to the use of modules of the perch unit for all proposed parcel widths.

Design Method : Analysis

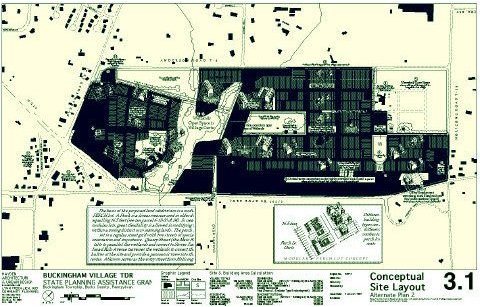

Data without analysis is useless. Analysis is the first step of design, thus the project area is analyzed, in a formal way, for constraints which helps to facilitate the exact problems that must be overcome in a successful solution. Likewise a successful solution will take advantage of found opportunities the site presents. In the Buckingham Village analysis, it was observed that the northwest corner of the site offered panoramic views, which the final solution responded to by making the location a gateway entry into the new village.

Design Method : Formulation of Goals and Objectives

The RFP and previous studies express many goals for the project. The consultant can facilitate the development of goals but goals need to be derived from the client advisory members or broader public interaction and should be structured around accepted public concepts for consensus building. To be successful, goals cannot be generalized but must be specific as possible without prescribing a physical solution that may later restrict design options. General and overly abstract goals waste time and effort and do not further the planning process. Goals should then be prioritized.

Design Method : Develop and Evaluation of Solutions

Fundamental to all design professions is the creative/evaluative cycle. In rational methodology, this occurs in three phases: 1) the generation of several competing alternative concepts; 2) The elaboration of selected concepts into workable solutions; and 3) the evaluation of solutions based on developed criteria.

The more complex the problem the less likely that the obvious solution will be the best. Thus several solutions must be developed. Generally unique solutions will be based on unique organizing principals. To explain by way of example: in the design of a new town layout we investigated three unique solutions: new village model (following Peter Calthorpe), traditional town model (based on Newtown Borough), and an urban ecology model. At the beginning of the project I was certain that a traditional town layout would be the successful solution. However, the opportunity to objectively compare the alternative urban forms for this site proved that the urban ecology model was a better fit due to the wetlands and quarry features that were integrated as the focus of the community. The project was later honored by inclusion in “The Architecture of Sustainable Communities” exhibit.

The process of evaluating options must be described in brief. Competing solutions are evaluated for the resolution of site constraints, the integration of site opportunities and compliance with the goals and objections of the planning criteria. In more formal analysis (or politically charged environments) the evaluation criteria is weighted and solutions receive a score to further objectify the analysis. The goal in this step is to lay bare the performance standards used in selecting the chosen solution or solutions (multiple option solutions are often preferable). Evaluation is typically focused on physical development however, economic and social impacts should be included as part of the evaluation criteria. The evaluation criteria can never be truly comprehensive and practically should be limited what can be listed on a single page.

Design Method : Policies, Plan and Guidelines

This represents the end product of the consultant’s effort. We will narrow our discussion to developing a policy and design framework which will define a successful physical solution. The following is in addition to documentation of the preceding steps of data collection, analysis, development of concepts, and evaluation.

Vision Statement

Conceptual Site Layout

Urban Design guidelines

Building Design guidelines

Shared Parking Analysis

Land Use Plan

Zoning District recommendation

Zoning Ordinance recommendations

Phasing and Implementation plans

The completion of one or more of these services signify the end of our typical urban design process.